In the two months leading up to Christmas, I spent two days per week on placement at two psychiatric hospitals. This was part of of my psychotherapy training – giving me a fuller view of mental illness and our mental health system, whilst also helping me understand the limitations of psychotherapy. This blog outlines what I learned from my placements at two psychiatric hospitals.

I observed psychiatrists, psychologists, occupational therapists, nurses and care staff. I read about, observed, sat and talked with patients (or ‘service users’). I attended ward rounds and joined Multi-Disciplinary Team meetings as hospital staff, family members and community care specialists discussed patients’ care plans.

I found this experience to be richly rewarding, enlightening, humbling, touching and, at times, distressing and saddening.

Acute Mental Illness Unit

I spent November in the male and female acute psychiatric wards of an NHS hospital.The purpose of such acute settings is to diagnose and treat patients who are experiencing severe mental ill health such as schizophrenia, drug-induced psychosis, bipolar disorder and suicidal depression.

Patients who arrive in crisis are usually ‘Sectioned’ (detained under the Mental Health Act) for their own safety – initially for up to 28 days under a ‘Section 2’ order – to undergo treatment and establish a working diagnosis.They are stabilised, generally using anti-psychotic medication, until the consultant psychiatrist deems they are no longer a risk to themselves (or to others, in rare cases).Such patients are then discharged to continue their recovery under the care of their community mental health/rehabilitation teams.

Those patients whose symptoms are insufficiently diminished after 28 days are often transferred to a ‘Section 3’ and detained for a further period of up to 6 months to allow for more treatment.This may include psychological input, electroconvulsive therapy (sending electrical charges to the brain) and/or trying out a range of different medications.

Those patients whose symptoms are insufficiently diminished after 28 days are often transferred to a ‘Section 3’ and detained for a further period of up to 6 months to allow for more treatment.This may include psychological input, electroconvulsive therapy (sending electrical charges to the brain) and/or trying out a range of different medications.

During my time at this hospital, I saw a wide variety of patient presentations and outcomes:

- There were those whose symptoms eased relatively quickly and were successfully discharged back to the community. Many people experience a psychotic episode due to an acutely stressful event (e.g. relationship breakup, work stress, drug misuse) and make a full and swift recovery.

- Some patients had been in hospital for months or years. Many of these have ’treatment-resistant schizophrenia’, meaning that medication has little or no impact on their symptoms and, therefore, are unlikely to be able to live safely and independently in a community setting.

- There were others who, after discharge or whilst on temporary ‘leave’ to their home, relapsed and had to be quickly readmitted to the acute psychiatric ward. Several of those were ‘revolving door’ patients, who struggle to stay well in the community and have cycled in and out of psychiatric units for many years.

- There were others who arrived at the hospital in severe distress. They had to be placed in a seclusion room with nothing but a thin mattress inside in order to minimise their risk of harm. Such individuals may have been experiencing auditory, visual or kinaesthetic hallucinations, delusions, intense paranoia and/or disordered thinking. Many were fearful. Some were aggressive…beneath that aggression was fear and confusion. I was surprised at how quickly and profoundly the behaviour of such individuals changed – a testament to the strength of the medication they were often forcibly administered.

One gentleman I saw acted in a threatening and abusive way towards staff when he arrived. He was placed in seclusion and then went into a catatonic state. He lay face down on the floor for two days, the only sign of life being his steady breathing. After two days, he ‘awoke’, was chatting with staff without aggression and was moved into the communal ward.

One lady had clearly been unwell for many months. I was quite astonished that nobody had reported their concerns about her wellbeing to support services. Lack of self-care often goes hand-in-hand with severe mental illness. This lady had become so painfully thin that her trousers would not stay up…but patients are not allowed belts due to the risk of ligature. She had matted hair and wore dirty clothes. Her home was full of rubbish and infested with vermin. Her behaviour was erratic and she believed she had supernatural powers. In the first few psychiatric consultations I observed, she barely engaged and, when she did, she was very distracted, quiet, meek and we struggled to make sense of what he said. Over time, an appropriate combination of medications and skilful, compassionate staff interventions led to her becoming increasingly coherent, self-confident and attentive to her self-care.

Another gentleman felt that he was being detained on the psychiatric ward for no reason, believing there was absolutely “nothing wrong” with him. However, he was tortured by paranoid thoughts and was convinced that his family were ‘out to get him’. And this is the paradox of psychosis: those who are unwell often lack the insight to appreciate that they have become unwell; their reality is ‘normal’. So how do such people respond when they are detained in a psychiatric hospital against their will? Some get angry and frustrated. Some lose hope and motivation, falling into depression and abandoning their self-care. Some refuse to take medication; they then either become more intensely unwell or have medication forced upon them. Others try to ‘say the right things’ to convince professionals that they are well, in the hope that they will be discharged.

For me, addressing the causes of distress in a holistic, joined-up manner is key to recovery. I was pleased to see regular engagement with patient’s families, community mental health, social care and occupational health teams. The community teams do the best they can to support vulnerable individuals in the community. Sadly, like many parts of the NHS, they seem to be woefully under-staffed, limiting the amount of support that those vulnerable individuals can receive and, therefore, increasing the chances of them relapsing. There also appears to be a high turnover of community care staff, which must make it hard for service users to maintain the kind of trusting, understanding, personal relationship that would support their ongoing recovery.

For me, addressing the causes of distress in a holistic, joined-up manner is key to recovery. I was pleased to see regular engagement with patient’s families, community mental health, social care and occupational health teams. The community teams do the best they can to support vulnerable individuals in the community. Sadly, like many parts of the NHS, they seem to be woefully under-staffed, limiting the amount of support that those vulnerable individuals can receive and, therefore, increasing the chances of them relapsing. There also appears to be a high turnover of community care staff, which must make it hard for service users to maintain the kind of trusting, understanding, personal relationship that would support their ongoing recovery.

I have learnt that talking therapy is not always effective, notably with patients who are experiencing severe psychosis. However, whilst I am mindful that such acute units exist to deal with crises, it saddened me that talking therapy is not more integrated into many individuals’ ongoing care plans, perhaps due to a lack of funding.

Many of the patients I saw have enduring mental health issues, exacerbated by their past traumas and daily stresses. When they are discharged back to the community, many of misuse substances to cope with their pain. Such numbing behaviours often leading to further deterioration in their mental health and, often, readmission to the psychiatric unit.

This became poignantly clear to me when I sat in on a psychological debrief meeting with staff who had, two days earlier, dealt with a patient’s suicide on their ward. I was truly humbled by the passion, dedication and care the nursing staff embodied. They pulled together and supported each other with almost super-human humanity after a 15-hour shift that had ended in tragedy – the second such traumatic event in six weeks. And all this despite the pressures of Covid and chronic staff shortages that is evidently resulting in exhaustion, overwhelm and a plethora of holistic health issues. Many nursing and psychiatric staff are understandably leaving their roles, whilst others stoically and heroically remain despite not feeling clinically safe in their working environment. This I found very saddening.

Community Rehab Unit

I spent December in a small Community Rehab Unit, a low-secure psychiatric hospital which serves as a stepping stone for those who have been discharged from an acute psychiatric ward. This was a much less intense and more relaxed environment than the acute ward. Here I was grateful and, at times, uplifted to observe the next phase of patients’ recovery journeys, as they took steps towards a degree of independent community living.

Patients here were supported by an occupational therapist, a psychologist, mental health nurses and other care staff. As well as ongoing medication and, where appropriate, 1:1 psychology sessions, patients are supported with ‘Activities of Daily Living’ such as laundry, cooking skills, budgeting, exercise and other self-care interventions. When staffing and funding allowed, group activity sessions were organised, including mindfulness, creativity and trips out into the community.

However, motivating many of the patients to engage in group activities, self-care and autonomy appeared to be a constant challenge. One of the common side effects of anti-psychotic drugs is to reduce energy and motivation. Many of the patients spent most of their days in a passive, lethargic cycle of sleeping, eating, smoking and watching television. Despite the nursing staff’s messages around healthy eating, virtually all of the patients indulged their large appetites (another side effect of their medication) and consumed excessive quantities of food high in fat, salt and/or sugar. This led to health issues including diabetes.

However, motivating many of the patients to engage in group activities, self-care and autonomy appeared to be a constant challenge. One of the common side effects of anti-psychotic drugs is to reduce energy and motivation. Many of the patients spent most of their days in a passive, lethargic cycle of sleeping, eating, smoking and watching television. Despite the nursing staff’s messages around healthy eating, virtually all of the patients indulged their large appetites (another side effect of their medication) and consumed excessive quantities of food high in fat, salt and/or sugar. This led to health issues including diabetes.

Again, I met a wide variety of individuals with a wide variety of needs and outcomes.

- Some patients were a long way from being ready to live in the community, whether that be in supported living accommodation or independently.

- Others appeared to be ready to take their next step but then had a relapse. After an extended period with intense professional support, patients can become institutionalised; the prospect of looking after themselves and being alone in the world may become overwhelming. The pressures of daily living mount, including access to alcohol and other drugs, stresses around relationship, finances, housing, work and a lack of structure, routine, purpose and meaning.

I heard about many service users who, on discharge, either failed to engage with their community support team, stopped taking their medication, reverted to unhelpful behaviours and/or did not get the sufficient support due to lack of staff/funds. Such individuals often have to return to hospital for more treatment and support. One such example was a lady who was imminently due to move into supported housing but then absconded from the unit. The voices in her head that encouraged her to act in impulsive and dangerous ways had become more intense. Thankfully, the police apprehended her and averted a potentially very harmful crisis.

I heard about many service users who, on discharge, either failed to engage with their community support team, stopped taking their medication, reverted to unhelpful behaviours and/or did not get the sufficient support due to lack of staff/funds. Such individuals often have to return to hospital for more treatment and support. One such example was a lady who was imminently due to move into supported housing but then absconded from the unit. The voices in her head that encouraged her to act in impulsive and dangerous ways had become more intense. Thankfully, the police apprehended her and averted a potentially very harmful crisis. - I was truly heartened to witness numerous individuals transitioning to live well in the community, which brought joy to service users and staff alike. Many such individuals enjoy the kind of fruitful relationships, fulfilling careers and positive self-esteem that can go hand-in-hand with living independently with an appropriate support network.

What I have learned

I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to spend time in two psychiatric hospitals, getting to know the systems and pathways, the staff and the patients. It has been a truly humbling experience that has changed me and how I see others. I take away much learning about the patients, the NHS mental health services and also about recovery from mental ill health.

Firstly, I now have a better understanding of the individual souls beneath the diagnoses of severe mental health issues. I have sat with a lady who was imprisoned for attempted murder, a convicted paedophile and a man who spent half of his earnings on drugs every week. It would be easy to brand such folk as ‘evil’ or ‘bad’. I also sat with a man who attempted to throw himself off the roof of a tower block – twice, a young lady who had been raped many times and a lady who was tortured by the belief that her children had been imprisoned and were being routinely abused.

Perhaps, for many of us, it would be easier to sympathise with this latter group and we would be less likely to label them as ‘bad’ individuals. Mental ill health takes many forms and has many underlying factors. It has been a privilege to see the human beings behind the ‘headline’ behaviours and diagnoses. As I teach on my Mental Health First Aid courses, there is a common misconception around psychosis. The media likes to sensationalise such diagnoses, painting those experiencing severe mental ill health as dangerous, raging lunatics who are hell-bent on murderous violence, unprovoked aggression and destruction. In reality, people who are experiencing a psychotic episode are almost always confused, scared and overwhelmed. Such people are much more likely to be a risk to themselves than anybody else – violence towards others is very rare.

During the past two months, I have heard patients’ backstories; tales of intense historical traumas, aspects of life and daily challenges of which I have little direct experience.  We may be quick to judge, blame, dismiss or avoid people with whom we may struggle to relate – ignorance may feel like bliss but also promotes fear, hatred and division. Whilst it may be harder to do, I always find it humbling and enlightening to connect with others in order to better understand them. Proximity leads to understanding and compassion. Every individual I met in those two hospitals was a human being who had suffered multiple traumas and was confused, hurt and scared.

We may be quick to judge, blame, dismiss or avoid people with whom we may struggle to relate – ignorance may feel like bliss but also promotes fear, hatred and division. Whilst it may be harder to do, I always find it humbling and enlightening to connect with others in order to better understand them. Proximity leads to understanding and compassion. Every individual I met in those two hospitals was a human being who had suffered multiple traumas and was confused, hurt and scared.

Secondly, I feel I have gained a broader understanding of how the NHS treats those experiencing severe mental ill health. What I am left with is mixture of two opposing emotions. On one hand, I am so touched and inspired by the psychiatric staff’s strength of spirit and selfless devotion to support the vulnerable souls in their care. On the other hand, I am truly saddened and angry that such services are under so much pressure. The pressure, I believe, comes from inappropriate funding and also the societal issues that are creating the conditions for the mental health crisis we are in the midst of.

This relatively brief experience of one setting by no means makes me an expert on NHS mental health services. Clearly, the NHS is a wonderful organisation filled with wonderful people. Sadly, it appears to be creaking at the seams. How do we change this unsustainable situation? Well, prevention is better than cure, so I suggest we need to look at the causes of mental ill health and address those from the bottom up. And, when people do become unwell, they need the best care to help them through their crisis. Crucially, this support must continue throughout their recovery. That means providing properly-funded, joined up services staffed by (com)passionate, qualified frontline staff, supported by (com)passionate managers who have a real understanding of both their staff and their service users’ needs

Finally, this experience has strengthened my beliefs around the key factors that promote recovery from mental ill health. For me, the seven crucial factors are:

- Hope. There is always hope for recovery and there is no recovery without hope. This hope has to live within the individual and those around them.

- Patience. Recovery is a very individual process. It takes as long as it takes and means different things to different people. For some, living well despite their ongoing symptoms represents recovery.

- Empowerment. It heartened me to witness psychiatrists involving patients in their choice of treatments. When professionals act in this way, it promotes self-belief, self-confidence and motivation.

- Compassion. Treating each ‘service user’ with respect and kindness whilst mindfully attending to their individual needs.

- Purpose. To maintain recovery, individuals must have a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives;

- Will. The individual has to truly want to get well. They must engage in their recovery with belief, self-discipline and determination.

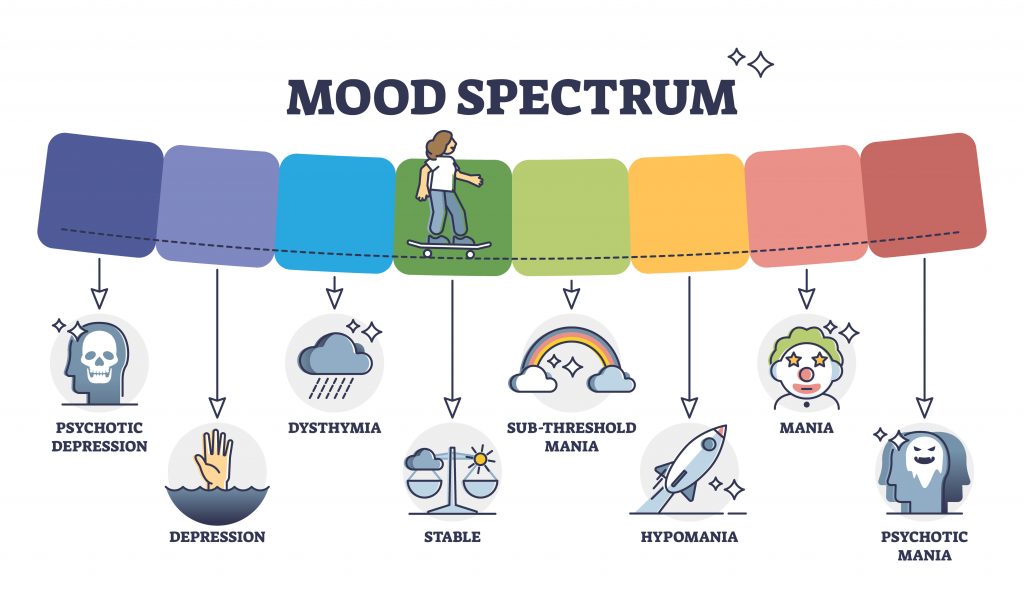

- Ongoing support. Mental health is a continuum – we are not either 100% well or 100% unwell. So, when patients are discharged from hospital, they need ongoing, tailored, holistic support from an appropriate combination of community services, friends and family. This often includes a combination of medication, talking therapy, social and practical support.

In sharing my experiences, I hope that readers will be inspired to see the human beings beneath the diagnoses and stigma around severe mental illness. I hope that readers will understand more, delve more, be more hopeful, more compassionate and less fearful of the unknown.

Some details have been changed in order to protect patient confidentiality.

Further information and support

Information on psychosis:

- https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/psychosis/overview/

- https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/psychosis/about-psychosis/

For information on how Pathlight can support you, your family or your organisation around mental health, relationships, workplace wellbeing and more, please get in touch:

- Click here to sign up to Pathlight’s e-newsletter for occasional updates on our services, resources to support mental health & wellbeing and more.

- Visit our website or email us for details of our services

- Mental Health First Aid training

- Workplace wellbeing programmes

- Coaching for individuals, families and teams

- Webinars for individuals and organisations

For more information on this blog post, interviews or services provided by Pathlight Ltd, please email Paul: info@pathlight.org.uk